UIUCTF 2024: Groups

Published:

I played UIUCTF with b01lers this weekend. I was not planning on playing it initially because I had to finish up some research work and internship stuffs, but someone pinged me in the b01lers Discord server asking if I have any thoughts on this particular challenge, which made me take a look.

As a member of b01lers, I am meant to have some geopolitical rivalries (? lol) with SIGPwny (the team that hosts UIUCTF).1 But near the end, I wished I could spend more time on this competition because I was able to tell just by reading the challenges that they are written very well and with care. So, thank you, SIGPwny, for giving me a productive yet reinvigorating break from my grad school and intern work. It was fun!

As of right now, the CTF website is still alive, and click this for the CTFTime event page.

I discussed this challenge with CygnusX, enigcryptist, and VinhChilling.

Challenge Description

crypto/Groups

Author: NikhillMy friend told me that cryptography is unbreakable if moduli are Carmichael numbers instead of primes. I decided to use this CTF to test out this theory.

ncat --ssl groups.chal.uiuc.tf 1337

We are provided a Python script challenge.py, which the server runs upon connecting:

"""challenge.py"""

from random import randint

from math import gcd, log

import time

from Crypto.Util.number import *

def check(n, iterations=50):

if isPrime(n):

return False

i = 0

while i < iterations:

a = randint(2, n - 1)

if gcd(a, n) == 1:

i += 1

if pow(a, n - 1, n) != 1:

return False

return True

def generate_challenge(c):

a = randint(2, c - 1)

while gcd(a, c) != 1:

a = randint(2, c - 1)

k = randint(2, c - 1)

return (a, pow(a, k, c))

def get_flag():

with open('flag.txt', 'r') as f:

return f.read()

if __name__ == '__main__':

c = int(input('c = '))

if log(c, 2) < 512:

print(f'c must be least 512 bits large.')

elif not check(c):

print(f'No cheating!')

else:

a, b = generate_challenge(c)

print(f'a = {a}')

print(f'a^k = {b} (mod c)')

k = int(input('k = '))

if pow(a, k, c) == b:

print(get_flag())

else:

print('Wrong k')

Challenge Explained

The server takes a 512-bit (or larger) integer, say $n$, as an input and do the following inspections:

- Check whether $n$ is a prime number or not.

- Randomly picks a non-identity element $a \in \mathbb{Z}_n^\times$ and tests whether $a^{n-1} \equiv 1 \; (\text{mod } n)$ or not; repeats this 50 times.

"""From challenge.py"""

def check(n, iterations=50):

if isPrime(n):

return False

i = 0

while i < iterations:

a = randint(2, n - 1)

if gcd(a, n) == 1:

i += 1

if pow(a, n - 1, n) != 1:

return False

return True

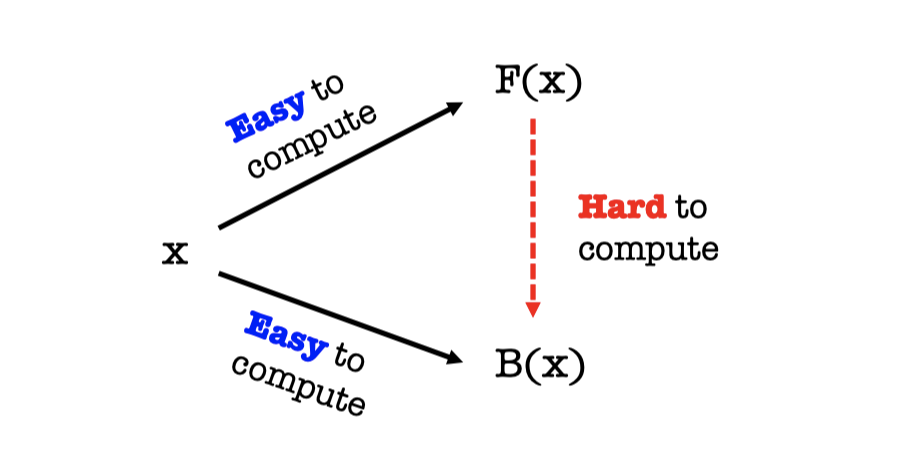

Once we pass this initial screening, we are asked to solve a discrete log problem. The server chooses a random $a \in \mathbb{Z}_n^\times$ and $2 \leq k \leq n-1$, returns $a$ and $a^k$, and then asks us to figure out $k$ given those two values.

"""From challenge.py"""

...

def generate_challenge(c):

a = randint(2, c - 1)

while gcd(a, c) != 1:

a = randint(2, c - 1)

k = randint(2, c - 1)

return (a, pow(a, k, c))

...

if __name__ == '__main__':

...

a, b = generate_challenge(c)

print(f'a = {a}')

print(f'a^k = {b} (mod c)')

k = int(input('k = '))

if pow(a, k, c) == b:

print(get_flag())

By Fermat's little theorem, if $n$ is prime then $a^{n-1} \equiv 1 \; (\text{mod } n)$ holds for all $a \in \mathbb{Z}_n^\times$. But unfortunately, in this challenge, we are forced to pick a composite $n$. The program tests whether a randomly picked $a \in \mathbb{Z}_n^\times$ satisfies the equation $a^{n-1} \equiv 1 \; (\text{mod } n)$ or not 50 times only. However, since $a$ is picked randomly, it is likely very difficult to create a custom $n$ that passes the test exactly 50 times or higher. That is, giving an $n$ that actually satisfies $a^{n-1} \equiv 1 \; (\text{mod } n)$ at all times is desired (but again, $n$ is not prime).

Towards the Flag

Attempt 1

The converse of Fermat's little theorem is not true in general. There are composite numbers where Fermat's little theorem still holds and they are called, as the challenge description spoiled already, Carmichael numbers.

The Wikipedia page for Carmichael numbers has a very large Carmichael number as an example:

\[\begin{align*} n & = p (313(p-1)+1) (353(p-1)+1) \text{ where } p = 2967 \dots 2883 \end{align*}\]which is a very large number $n = 2887\dots5867$. Giving this number as input to the server works, but the problem is, we have to solve a discrete log problem:

$ ncat --ssl groups.chal.uiuc.tf 1337

c = 2887148238050771212671429597130393991977609459279722700926516024197432303799152733116328983144639225941977803110929349655578418949441740933805615113979999421542416933972905423711002751042080134966731755152859226962916775325475044445856101949404200039904432116776619949629539250452698719329070373564032273701278453899126120309244841494728976885406024976768122077071687938121709811322297802059565867

a = 1975016391437489347152459493806681895282540000360321467745861197592098677397350778549597420091790822945400527392816232786147030074665760129259390772932883232233142153767669286722296193413190718612194099179275550927429961917142906803188424117649703624333854906213065703553669325385753806559627721483855111710416792149299653489063349052766908959806850869746537811074001131239176588967281259848424178

a^k = 717255315335586350352011829698498537528457997952781551465428088895097647054311420626596999331630075938662223716946862468511880181955262362590566039965581179681185651000951832396154915011729138762610582275831154370225733504488421624501188449647149863721442605672401117357879283455382750030212227546686999752228809286358835209051215872552721177006085311506202041449010800832165509976262067150533739 (mod c)

k =

which Sage's discrete_log function seemingly cannot handle. (For clarity: In above, c is our input ($n$), and a and a^k are the responses from the server.)

n = 2887148238050771212671429597130393991977609459279722700926516024197432303799152733116328983144639225941977803110929349655578418949441740933805615113979999421542416933972905423711002751042080134966731755152859226962916775325475044445856101949404200039904432116776619949629539250452698719329070373564032273701278453899126120309244841494728976885406024976768122077071687938121709811322297802059565867

a = Mod(1975016391437489347152459493806681895282540000360321467745861197592098677397350778549597420091790822945400527392816232786147030074665760129259390772932883232233142153767669286722296193413190718612194099179275550927429961917142906803188424117649703624333854906213065703553669325385753806559627721483855111710416792149299653489063349052766908959806850869746537811074001131239176588967281259848424178, n)

a_k = Mod(717255315335586350352011829698498537528457997952781551465428088895097647054311420626596999331630075938662223716946862468511880181955262362590566039965581179681185651000951832396154915011729138762610582275831154370225733504488421624501188449647149863721442605672401117357879283455382750030212227546686999752228809286358835209051215872552721177006085311506202041449010800832165509976262067150533739, n)

discrete_log(a_k, a)

# Takes forever, even with discrete_log_lambda.

Attempt 2

Carmichael numbers must have at least three distinct prime factors. This was proved by Chernick a long time ago. Chernick also proved that, every number of the form $(6k+1)(12k+1)(18k+1)$ is a Carmichael number if $6k+1$, $12k+1$, and $18k+1$ are all primes. Allegedly, this is the most commonly used method today for generating large Carmichael numbers.

I could not find any list of large Carmichael numbers (512-bit or larger) anywhere online including OEIS and research papers. Then, I found this StackExchange post that has the following Carmichael number:

\[\begin{align*} n & = (6k+1)(12k+1)(18k+1) \text{ where } k = 10^{170} + 8786356 \end{align*}\]which gives $n = 1296\dots5009$. But evidently, Sage still cannot handle this.

$ ncat --ssl groups.chal.uiuc.tf 1337

c = 1296000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000341613525240000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000030015380819675955600000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000879086081381222878165009

a = 652404532758647182618998066096190441585359198494837473517078845664741765921912464496830642421144474846548097093757384397135999711495290953909360085887323537525323414455018207352854417520771750204240082119395316123659092277067148159332757782816117097582049434253664674135220735120208514664053517990095593829345204383932051181752853865595114999751596084356593165343177711295804633834619146641241654423340194291383224354286751014503828445881721077332545674308459216498274850635219484931191763237919006784369324532755

a^k = 517944182958120633296942637817438790198151994830203409646608730159625351204863416614139157238969670458361376135069725354923344795618201834004173670059459355179962205398706490013840562669626634681616003376281538991453536024595102938901880981584621313776712330436172261727871727803891374245946355592577818635414476188590672210879616750401507100756977985342374895373332156639411899085713741604148712505309186155005402109704698856237458793208276973075422620091622984857970131201058717150569815276793996821966645796092 (mod c)

k =

m = 10^170 + 8786356

n = (6 * m + 1) * (12 * m + 1) * (18 * m + 1)

a = Mod(652404532758647182618998066096190441585359198494837473517078845664741765921912464496830642421144474846548097093757384397135999711495290953909360085887323537525323414455018207352854417520771750204240082119395316123659092277067148159332757782816117097582049434253664674135220735120208514664053517990095593829345204383932051181752853865595114999751596084356593165343177711295804633834619146641241654423340194291383224354286751014503828445881721077332545674308459216498274850635219484931191763237919006784369324532755, n)

a_k = Mod(517944182958120633296942637817438790198151994830203409646608730159625351204863416614139157238969670458361376135069725354923344795618201834004173670059459355179962205398706490013840562669626634681616003376281538991453536024595102938901880981584621313776712330436172261727871727803891374245946355592577818635414476188590672210879616750401507100756977985342374895373332156639411899085713741604148712505309186155005402109704698856237458793208276973075422620091622984857970131201058717150569815276793996821966645796092, n)

discrete_log(a_k, a)

# Again takes forever :-/

Attempt 3 (Flag!)

I think this is a good time to change our plan slightly. Recall that the security of RSA stems from the fact (assumption, more accurately) that the integer factorization problem is computationally difficult. The modulus $n$ in RSA is chosen as a product of two primes $n = pq$. But why? Why not, say, $n = pqr$?

This is because the security parameters, which in this case is the number of bits, are constants. For example, RSA-2048 uses 2048-bit modulus $n$. Roughly speaking, if $n$ is a multiple of three primes, namely $n = pqr$, then $p$, $q$, and $r$ should be around $682$-bit. And if $n = pq$ then $p$ and $q$ are around $1024$-bit. Clearly, when factors are smaller, then it is easier to factor, and hence having more factors can only be detrimental.

Although this challenge isn't exactly about RSA, if the modulus can be factorized into small factors, then the discrete log problem can also be solved easily using the Chinese remainder theorem and whatnot. As far as I know, Sage's discrete_log function does all that for you automatically.

This gives some motivations that we should look for other methods for finding large Carmichael numbers. I remembered that Erdos has a work on it, which I think is usually referred to as Erdos' method, but I don't think it has any formal name that everyone agrees on. It is explained pretty well in many places online, though I recommend this paper by Guillaume and Morain.

Anyway, the method goes as follows:

- Choose a large natural number $\Lambda$ that is even and (highly preferably) has a large number of factors.

- Find all primes $p$ such that $p - 1 \mid \Lambda$ yet $p \not\mid \Lambda$. Denote the set of all such $p$'s as $P$.

- Find $S \subseteq P$ such that $n := \prod_{p \in S} p \equiv 1 \; (\text{mod } \Lambda)$.

- Return $n$.

The correctness of this algorithm comes directly from the fact that $n$ is a Carmichael number if $\lambda(n) \mid n-1$ where $\lambda(n)$ is the Carmichael function defined to be the LCM of $(p_i - 1)$'s where $p_i$'s are prime factors of $n$.

Now the question is: What $\Lambda$ should we choose for this problem? Every $\Lambda$ in the paper by Guillaume and Morain seems too large for my machine. For example:

Lambda = 2^14 * 3^7 * 5^4 * 7^2 * 11^2 * 13^2 * 17 * 19 * 23 * 29 * 31 * 37 * 41 * 43 * 47

P = []

for p in prime_range(Lambda -1):

if Lambda % (p-1) == 0 and Lambda % p != 0:

P.append(p)

print(P)

print(len(P)) ## Almost had my computer get frozen.

But if you think about it: we might not need a large $\Lambda$. We want $n = \prod_{p \in S} p$ to be large enough (512-bit or longer), and that might be achievable even with a not-very-large $\Lambda$.

A few minutes later, I found this paper by Loh and Neibuhr that has lists of $\Lambda$'s that they managed to generate Carmichael numbers from. I just picked one that looks still large enough and ran my code again. Finally, my code managed to return something fast!

Lambda = 554400

## Taken from Loh and Neibuhr '96 (Mathematics of computation, 65(214), pp.823-836.)

P = []

for p in prime_range(Lambda -1):

if Lambda % (p-1) == 0 and Lambda % p != 0:

P.append(p)

print(len(P)) ## 71

print(P) ## [13, 17, 19, 23, 29, 31, 37, 41, 43, 61, 67, 71, 73, 89, 97, 101, 113, 127, 151, 181, 199, 211, 241, 281, 331, 337, 353, 397, 401, 421, 463, 601, 617, 631, 661, 673, 701, 881, 991, 1009, 1051, 1201, 1321, 1801, 2017, 2311, 2521, 2801, 3169, 3301, 3361, 3697, 3851, 4201, 4621, 4951, 5281, 6301, 7393, 9241, 9901, 11551, 12601, 15401, 18481, 19801, 34651, 55441, 79201, 92401, 110881]

It'd be great if we can enumerate over all $S \subseteq P$, but that'd take too long. Let's compute the minimum number of elements we need to multiply to get a 512-bit integer.

i = 0

prod_so_far = 1

while i < len(P):

prod_so_far *= P[i]

if len(bin(prod_so_far)[2:]) > 512:

break

i += 1

num_for_512 = i

print("num_for_512", num_for_512) ## 59

This gives us where we can start from. This is also how I chose my Lambda from the list in that paper: of course, len(P) should be larger than num_for_512, yet the difference between the two is small enough so my computer can get it done reasonably fast.

P_above_100 = [p for p in P if p > 100]

for S in Subsets(P, num_for_512):

prod_S = prod(S)

if prod_S % Lambda == 1 and len(bin(prod_S)[:2]) >= 512:

print("Found it")

print(prod(S), S)

## 916350764286257743747495117302849071847706509790137622084257374486742072002708971608925169887714141197238574744721669078992288616293876485589111443955109384001

## {2311, 1801, 3851, 13, 397, 4621, 17, 401, 19, 661, 23, 151, 281, 1051, 29, 31, 673, 110881, 37, 421, 41, 1321, 43, 9901, 1201, 18481, 181, 61, 701, 67, 71, 199, 73, 331, 463, 337, 211, 4951, 89, 601, 2521, 991, 97, 353, 2017, 3169, 101, 3301, 7393, 79201, 617, 113, 241, 881, 1009, 2801, 92401, 631, 127}

break

print("None")

Voila! As intended/hoped, generating this output takes only a few seconds. Now we just need to get it all together, and we are done!

import pwn

nc_ed = pwn.remote('groups.chal.uiuc.tf', '1337', ssl=True)

nc_ed.recvuntil("c = ")

c = prod(S)

nc_ed.sendline(str(c))

print(str(c))

a = nc_ed.recvline()

a = str(a)[6:-3]

a_k = nc_ed.recvline()

a_k = str(a_k)[8:-11]

a = Mod(int(a), c)

a_k = Mod(int(a_k), c)

nc_ed.recvuntil("k = ")

nc_ed.sendline(str(discrete_log(a_k, a)))

nc_ed.recv()

""" b'uiuctf{c4rm1ch43l_7adb8e2f019bb4e0e8cd54e92bb6e3893}\n' """

Beautiful.

Flag: uiuctf{c4rm1ch43l_7adb8e2f019bb4e0e8cd54e92bb6e3893}

I'd say this was more a computational number theory problem than a cryptography problem, but still it is crypto-related enough to be called a crypto chall. And regardless, it was fun.

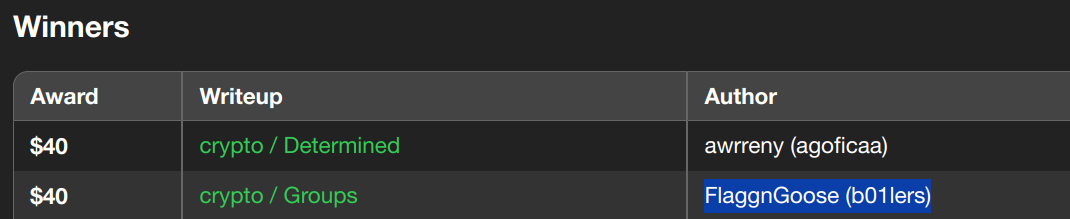

Epilogue

This post was apparently selected as one of the best writeups by the UIUCTF organizers. Thank you again, SIGPwny!

I was reading my solution again, and I think I could've stopped at my second attempt. I mentioned there that my $n = (6k+1)(12k+1)(18k+1)$ was too large for my SageMath to handle. That might be true, but we know the full prime factorization of $n$ already, and we can even compute $\varphi(n)$ ourselves:

\[ \varphi(n) = 6k \cdot 12k \cdot 18k \]So, we could have just called Pohlig-Hellman with $\varphi(n)$ instead. The issue was that, we knew the prime factorization of $n$ already, but my SageMath didn't because I did not tell her, and hence it was too large for her to handle.

As always, attention to detail is the key.

1. I hope my advisor doesn’t read this because he went to UIUC, lol. (Though, I don’t think he was involved in any SIGPwny activities.)

Updated: