Schauder Basis of Banach Spaces

Published:

I was once asked this question on the spot in a Discord server, but I shamefully (I’ll admit) gave a pretty bad answer to it. It was not a difficult or deep question, but I think it is worth spanning (pun intended) a blogpost.

The primary reference for this post is Schechter and Brezis. I also found this book chapter by Christopher Heil helpful.

TL;DR

For our average impatient readers who just want to see the answer and call it a day, here is the summary of this post:

Q. Does the set of vectors \(\mathcal{E} = \{ (1,0,0,0,\dots), (0,1,0,0,\dots), (0,0,1,0,\dots), \dots \}\) span $\ell_p$ space where $p$ is finite?

A. No. Counterexample: $(1,1/2,1/3,\dots) \in \ell_{p>1}$ but it is not a span of $\mathcal{E}$.

Wait, what?

I hope the TL;DR above was impactful enough to grab your attention. The sum $\sum_{n=1}^\infty 1/n$ diverges so clearly $(1,1/2,1/3,\dots) \notin \ell_{1}$, yet is $\in \ell_{p>1}$ by $p$-series test. Let $e_i = (0,\dots, 0,1,0,\dots)$ where the $1$ is in the $i$-th index and the rest are all zeroes so $\mathcal{E} = \{ e_i \}_{i \in \mathbb{N}}$, then $$ \left( 1, \frac{1}{2}, \frac{1}{3}, \dots \right) = e_1 + \frac{1}{2} e_2 + \frac{1}{3} e_3 + \cdots = \sum_{n=1}^\infty \frac{1}{n} e_n $$ There seems to be no issues here! Why is $(1,1/2,1/3,\dots) \notin \mathrm{Span}(\mathcal{E})$?

(Closed) Linear Span

We need to remember here that $\ell_p$ is a vector space (again, Banach spaces are complete normed vector spaces). Bear with me and let us recite the axioms for vector spaces: $V$ is a (real) vector space if for all $f,g,h \in V$,

- $f+g \in V$.

- $(f+g)+h = f+(g+h)$.

- There exists $0 \in V$ s.t. $f+0 = f$ for all $f \in V$.

- For all $h \in V$, there is $-h \in V$ such that $h+(-h) = 0 \in V$.

- $f+g=g+f$.

- For all $\alpha \in \mathbb{R}$, $\alpha f \in V$.

- $\alpha (f+g) = \alpha f + \alpha g$.

- $(\alpha + \beta)f = \alpha f + \beta f$.

- $(\alpha \beta) f = \alpha(\beta f)$.

- $1 \cdot h = h$.

A vector space $V$ is a normed vector space if it satisfies the above axioms 1-9 and in addition:

- For all $h \in V$, there exists a real number $\| h \|$ called the norm of $h$. Basically, $\| \cdot \| \colon V \to \mathbb{R}_{\geq 0}$.

- For all $\alpha \in \mathbb{R}$, $\| \alpha f \| = |\alpha| \|f\|$.

- $\| h \| = 0$ iff $h = 0$.

- $\| f+g \| \leq \|f \| + \|g \|$ for all $f, g \in V$.

It is an easy exercise to prove that the axioms 11-14 imply the axiom 10. Lastly, we say a normed vector space $(V, | \cdot |)$ is complete if every Cauchy sequence converges:

- For all Cauchy sequence $\{h_n\}_{n \geq 1}$ (i.e. $\| h_n - h_m \| \to 0$ as $n,m \to \infty$), there exists $h \in V$ such that $\| h_n - h \| \to 0$ as $n \to \infty$.

That is, we say $(V, | \cdot |)$ is a Banach space (complete normed vector space) if it satisfies all 15 axioms.

These axioms coincide with everything we learned in our very average linear algebra course. However, it is also these axioms that is making our life hard here: there is nothing in the 15 axioms that guarantees everything to be well-defined and behaved for infinite sums!

This forces us to define only finite sums of vectors for defining spans, for arbitrary vector spaces. As we are not specifying any topology or norm, we cannot simply write an infinite sum and hope it is well-defined (converges and is unique) axiomatically; even if they are, choosing a different norm or topology may bring a drastically different notion of convergence.

One immediate instance is the commutativity (axiom 5); we learned in undergrad real analysis that switching the order of summations in an infinite series can be problematic unless certain conditions are met (Riemann rearrangement theorem).

In any case, the key takeaway here is that the basis might contain infinitely many elements, but only finite linear combinations should be considered:

Definition. Let $X$ be vector space over a field $\mathbb{F}$. A (Hamel) basis of $X$ is a subset $(e_i)_{i \in \mathcal{I}}$ in $V$ such that every $x \in X$ can be uniquely written as \[ x = \sum_{i \in I} a_i e_i \] where $I \subseteq \mathcal{I}$ is finite and $a_i \in \mathbb{F}$.

Then, it is clear from the context that $\mathcal{E}$ does not span $\ell_p$, because any finite linear combination of elements of $\mathcal{E}$ will eventually be followed by an infinitely long sequence of zeros.

We do not have to lose our hope here though. Consider $x = (x_1, x_2, \dots) \in \ell_p$ and its ‘projection’ $x^{(N)} = (x_1, \dots, x_N, 0,0,\dots) \in \mathrm{Span}(\mathcal{E})$ (which clearly is a subset of $\ell_p$). Then, because $x \in \ell_p$,

\[\| x - x^{(N)} \|_p^p = \sum_{n = N+1}^{\infty} \lvert x_{n} \rvert^p \to 0 \text{ as } N \to \infty\]This shows that every $x \in \ell_p$ is either an element of $\mathrm{Span}(\mathcal{E})$ or is a limit point of $\mathrm{span}(\mathcal{E})$. So, $\mathrm{Span}(\mathcal{E})$ a dense subset of $\ell_p$, making $\ell_p = \overline{\mathrm{Span}(\mathcal{E})}$. And of course the closure is defined in terms of the topology induced by the $\ell_p$-norm.

In plain English: $\ell_p$ is in the closed linear span of the standard basis $\mathcal{E}$.

Introducing Schauder Basis

From the argument above, one may claim that the closed linear span of the standard basis $\mathcal{E} = \{e_1, e_2, \dots\}$ is equal to the set of convergent infinite sums $\sum_i a_i e_i$.

This claim is actually not true! Roughly put, the closed linear span considers all possible sequences of finite sums whose limits are taken; these ‘approximating’ sequences do not have to arise from a single infinite series with fixed coefficients, you can change the coefficients from one term to the next. Hence, the closed linear span can be bigger than the set of elements that can be written as an infinite sum (different sequences of approximations could converge to the same point).

This might not sound like too big of a deal for some people, understandably so. A little different way to put this is: the fact $\overline{\mathrm{Span}(\mathcal{E})} = X$ just tells us that one can approximation any element $x \in X$ using a finite linear combination of $\mathcal{E}$, without telling us how to approximate it and giving us any unique expansion of it.

Most crucially, dealing with Hamel basis turns out to be a headache in general; we can prove that there (arguably) cannot exist an explicit procedure for constructing a Hamel basis for every Banach space:

Theorem 1. Let $X$ be an infinite-dimensional Banach space and $\mathcal{E}$ be its Hamel basis. Then $\mathcal{E}$ exists, and is uncountably infinite.

In other words, an infinite-dimensional Banach space has uncountable dimension (even separable ones!).

As one might have anticipated already (because the statement that every vector space has a basis is equivalent to the axiom of choice), the proof of this theorem requires the use of the axiom of choice (Zorn’s lemma).

We shall also use the Baire Category Theorem, because we want to express $X$ as a countable union of subspaces, after assuming for the sake of contradiction that $\mathcal{E}$ is countable.

Baire Category Theorem. Let $X$ be a complete metric space and $\{X_n \}_{n \in \mathbb{N}}$ be a sequence of closed subsets in $X$ such that $X_n$ is nowhere dense, i.e. $\mathrm{Int}(X_n) = \emptyset$. Then, $$ X \neq \bigcup_{n \in \mathbb{N}} X_n \;\; \textsf{ but } \;\; \mathrm{Int}\left( \bigcup_{n \in \mathbb{N}} X_n \right) = \emptyset $$

For self-containedness’ sake, let us formally define what nowhere dense means.

Definition. Let $X$ be a normed vector space and $W$ is a set in $X$. $W$ is said to be nowhere dense in $X$ if for any open ball $\| x - x_0 \| < r$ in $X$, there always exists an element in it which does not belong to $\overline{W}$ (i.e. $\overline{W}$ contains no open balls).

Proof of Theorem 1. Let us first prove the existence. Let $S$ be the family of all subsets of $X$ that are linearly independent. Induce a poset $(S, \subseteq)$ where the partial order is inclusion $\subseteq$. Let $C$ be an arbitrary chain in $S$, then $C$ clearly has an upper bound: $U = \bigcup_{c \in C} c$ and it is in $S$ indeed. Then, by Zorn's lemma, $S$ has a maximal element, call it $\mathcal{E}$, and is a subset of $X$. Clearly, $\mathcal{E}$ spans $X$: if there existed an element $x \in X$ but $x \notin \mathrm{Span}(X)$, then $\mathcal{E} \cup \{x\}$ would still be linearly independent, contradicting the maximality.

Now let us prove the uncountability of $\mathcal{E}$. Suppose for the sake of contradiction that it is actually countable. Since $X$ is infinite-dimensional, assume $\mathcal{E}$ is infinite as well, that is, $\mathcal{E} = \{ e_i \}_{i \in \mathbb{N}}$.

For $n\in \mathbb{N}$, consider $X_n$ that is a vector space spanned by $\{e_i \}_{1 \leq i \leq n}$. As $X_n$ is finite dimensional and is a subspace of $X$ a complete normed space, it is also complete and hence is closed as well. It is however nowhere dense in the sense that its interior is empty (intuitively: imagine a plane in $\mathbb{R}^3$, it is impossible to place a ball in that plane in a way that it is entirely in the plane because it is bound to have a 'direction' such as the normal vector that the plane does not extend to).

But clearly, $X = \bigcup_{n\in \mathbb{N}} X_n$ (let $x \in X$ so that $x = \sum_{i=1}^k x_i e_{n_i}$, then $x \in F_{N}$ where $N = \max_{1\leq i \leq k} n_i$), meaning that a complete metric space is a countable union of closed nowhere dense sets. This contradicts the Baire category theorem. Hence, this proves the statement. $\blacksquare$

Theorem 1 is basically telling us that we cannot write elements of $X$ as finite sums in any manageable way. One might have seen this meme somewhere online, and this is where it comes from:

For all these reasons, we introduce Schauder basis over just talking about the closed linear span.

Definition. Let $X$ be a Banach space. A Schauder basis is a sequence $(e_i)_{i \geq 1}$ in $X$ such that for all $x \in X$ there exists a unique sequence $(x_i)_{i \geq 1}$ in $\mathbb{R}$ such that \[ x = \sum_{i=1}^\infty x_i e_i = \lim_{n \to \infty} \sum_{i=1}^n x_i e_i \]

Note that we denoted $(e_i)_{i \geq 1}$ as a 'sequence' this time, to emphasize that the order matters (because the series may not converge unconditionally), and there is a unique representation $(x_i)_{i \geq 1}$ of $x \in X$ accordingly. It is clear from the definition that the standard basis $\mathcal{E} = (e_i)_{i \geq 1}$ where $e_i = (0,\dots, 0, \underset{i\text{-th}}{1}, 0,\dots)$ that we have been discussing is a Schauder basis for $\ell_p$ for any $1 \leq p < \infty$.

(Non-)examples

From the example above, one may naively think that any basis that spans the space in a closed linear sense is a Schauder basis. But the existence or construction of a Schauder basis is not as trivial. An immediate example is $\ell_\infty$. The basis \( \mathcal{E} = (e_i)_ {i \geq 1} \) discussed above for $\ell_p$ is not a Schauder basis when $p = \infty$ because $x = (1,1,\dots) \in \ell_\infty$ because $| (1,1,\dots )|_ \infty = 1 < \infty$, but

\[\left\| x - \sum_{i=1}^N x_i e_i \right\|_\infty = \| (0,\dots, 0, 1,1,\dots) \|_\infty \to 1 \neq 0 \; \text{ as } \; N \to \infty\]A less immediate example is $C[0,1]$, the space of continuous real-valued functions on $[0,1]$ with the supremum norm:

\[\| f \|_\infty = \sup_{x \in [0,1]} \lvert f(x) \rvert\]Let $\mathcal{M} := \{1, x, x^2, \dots\}$ be the set of monomials, and its span is the set of all polynomials with finite terms. By Weierstrass approximation theorem, for any continuous real-valued function $f$ on a closed interval $[a,b]$, for all $\varepsilon > 0$ there exists a polynomial $p(x)$ such that $\| f - p \|_\infty < \varepsilon$ over $[a,b]$. So, $\mathrm{Span}(\mathcal{M})$ is dense in $C[0,1]$.

This leaves some possibility that $\mathcal{M}$ is a Schauder basis of $C[0,1]$, but it turns out it is not, because monomials are not “general” enough to represent every continuous function (intuitively: think about how not every continuous function can also be analytic). For instance, consider the following $f\colon [0,1] \to \mathbb{R}$ where:

\[f(x) = \begin{cases} 0 & \text{if } x \in [0,1/2] \\ x - 1/2 & \text{if } x \in [1/2, 1] \end{cases}\]Suppose there exists $(a_i)_{i \geq 0}$ such that $f_n(x) = \sum_{i=0}^n a_i x^i \to f(x)$ uniformly as $n \to \infty$. Then, because we should have $f_n(x) \to 0$ uniformly for all $x \in [0,1/2]$, it must be the case that $a_i = 0$ for all $i \geq 0$, but this is obviously problematic because it will also give $f_n(x) \to 0$ for $x \in [1/2, 1]$.

Fortunately, $C[0,1]$ does have a Schauder basis, called Faber-Schauder system. The construction goes as follows: let $\{ \tau_n \}_{n \geq 1}$ be a sequence of binary rationals such that

\[\tau_1 = 0, \; \tau_2 = 1, \; \tau_3 = \frac{1}{2}, \; \tau_4 = \frac{1}{4}, \; \tau_5 = \frac{3}{4}, \; \tau_6 = \frac{1}{8}, \; \tau_7 = \frac{3}{8}, \cdots\]and $\tau_n = \frac{1 + 2 (n-1) - 2^{\lfloor \log_2(n-1) + 1 \rfloor}}{2^{\lfloor \log_2(n-1) \rfloor + 1} }$, and the sequence of 'tent' functions $\phi_n \colon [0,1] \to [0,1]$ such that

\[\phi_n(t) = \begin{cases} 1 & \text{if } t = \tau_n \\ 0 & \text{otherwise} \end{cases}\]where $\phi_1 \equiv 1$ and $\phi_2(t) = t$ ($\phi_n \in C[0,1]$ for all $n \geq 1$ obviously). Using Archimedian property ($(\tau_{n})_{n \geq 1}$ are indeed dense in $[0,1]$) and the norm convergence property of $C[0,1]$ (which is uniform convergence), one can prove that $(\phi_n)_{n \geq 1}$ is indeed a Schauder basis of $C[0,1]$ (Archimedian property for existence and uniform convergence for uniqueness).

While abstract nonsense is the most interesting thing in the world, it would not hurt to step back and touch grass. Fourier basis $( \exp( \iota n x ) )_{n \in \mathbb{N}}$ is an orthonormal basis for $L^2[0,1]$, and it is indeed a Schauder basis. Its coefficients are uniquely determined as $\widehat{f}(n) = \left< f, e_n\right>_{L^2}$ and are indeed well-defined for all $f \in L^2$. The Fourier series $\sum_{n\geq 0} \widehat{f}(n) e_n \to f$ in $L^2$-norm thanks to Parseval's identity $\| f \|_{L^2}^2 = \sum_{n \geq 0} \lvert \widehat{f}(n) \rvert^2$ and Bessel's inequality $\sum_{n \geq 0} \lvert \left< f, e_n \right> \rvert \leq \| f \|_{L^2}^2$. It is, however, not a Schauder basis of $C[0,1]$. I will let the readers think about this more.

Inseparability

The 'intuitive/trivial basis' of $C[0,1]$ turns out to be not a (Schauder) basis, just as it was the case for $\ell_\infty$. Now the question is, can we also construct a Schauder basis for $\ell_\infty$?

Interestingly, it turns out $\ell_\infty$ does not have a Schauder basis. Even more interestingly, $\ell_\infty$ is not separable, and every inseparable Banach space has no Schauder basis! We shall prove this by proving its contrapositive.

Definition. A topological space $X$ is said to be separable if it contains a countable dense set; equivalently, $X$ is separable if there exists a sequence $(x_n)_{n \geq 1}$ such that every nonempty subset of $X$ contains at least one element in $(x_n)_{n \geq 1}$

Theorem 2. Let $X$ be a Banach space with a Schauder basis. Then $X$ is separable.

Proof of Theorem 2. Let $X$ be a Banach space with base field $\mathbb{K} = \mathbb{R}$ (the case with $\mathbb{C}$ can be done similarly) and $(e_i)_{i \geq 1}$ be its Schauder basis. Let $\widetilde{\mathbb{K}} = \mathbb{Q}$ (if $\mathbb{K} = \mathbb{C}$, then choose $\widetilde{\mathbb{K}} = \mathbb{Q} + \mathbb{Q}i$), and define a space \[ \widetilde{X} := \left\{ \sum_{i=1}^n a_i e_i : n \in \mathbb{N}, a_i \in \mathbb{K} \right\} \] Clearly $\widetilde{X}$ is countable, and so it suffices to prove $\widetilde{X}$ is dense. That is, given an arbitrary $\varepsilon > 0$ and element $x \in X$, we shall prove that there exists $\widetilde{x} \in \widetilde{X}$ such that $\| x - \widetilde{x} \| < \varepsilon$.

As $(e_i)_{i \geq 1}$ is a Schauder basis of $X$, we can write $x \in X$ uniquely as \[ x = \sum_{i=1}^{n} x_i e_i \] where $n \geq 1$ ($n$ is the number of elements in $(e_i)_{i \geq 1}$, and could be infinity). Because $\widetilde{\mathbb{K}}$ is dense in $\mathbb{K}$, for all $x_i \in \mathbb{K}$ there exists $\widetilde{x_i} \in \widetilde{\mathbb{K}}$ such that $\lvert x_i - \widetilde{x_i} \rvert < \varepsilon'$. Then, by setting $\widetilde{x}$ as the linear combination of Schauder basis with $\widetilde{x_i}$ as coefficients, \[ \begin{align*} \| x - \widetilde{x} \| = \left\| \sum_{i=1}^N (x_i - \widetilde{x_i}) e_i \right\| \leq \sum_{i=1}^N \lvert x_i - \widetilde{x_i} \rvert \| e_i \| \end{align*} \] Assuming WLOG $\| e_i \| = 1$ for all $i$ and choosing $\varepsilon' = \varepsilon / 2^i$ for each $i$ (recall $\lvert x_i - \widetilde{x_i} \rvert < \varepsilon'$), we can further bound the above expression as follows: \[ \begin{align*} \phantom{\| x - \widetilde{x} \| = \left\| \sum_{i=1}^N (x_i - \widetilde{x_i}) e_i \right\| } & \leq \sum_{i=1}^N \lvert x_i - \widetilde{x_i} \rvert \| e_i \| \\ & < \varepsilon \sum_{i=1}^n \frac{1}{2^i} \leq \varepsilon \end{align*} \] This completes the proof. $\blacksquare$

Now we shall show that $\ell_\infty$ is indeed not separable. This is one of my favorite proofs in functional analysis, because it reminds me of the proof of uncountability of $(0,1) \subseteq \mathbb{R}$.

Theorem 3. $\ell_\infty$ is not separable.

Proof of Theorem 3. For the sake of contradiction suppose $\ell_\infty$ is separable. Let $A \subseteq \ell_\infty$ be a countable and dense subset of $\ell_\infty$. Enumerate $A = \{ a^{(k)} \}_{k \geq 1}$ and denote $a^{(k)} = (a_1^{(k)}, a_2^{(k)}, \dots) \in \ell_\infty$. We shall construct $b \in \ell_\infty$ such that $b \notin \overline{A}$ to induce contradiction: let $b = (b_1, b_2, \dots) \in \ell_\infty$ such that \[ b_k = \begin{cases} a_k^{(k)} + 1 & \text{if } \lvert a_k^{(k)} \rvert \leq 1 \\ 0 & \text{otherwise} \end{cases} \] Then, $\| b - a^{(k)} \|_\infty \geq \lvert b_k - a_k^{(k)} \rvert \geq 1$ for all $k$, making $b \notin \overline{A}$. $\blacksquare$

It is an easy exercise to prove that $\ell_p$ for $1 \leq p < \infty$, as well as $c$, $c_0$, and $c_{00}$, are separable. Note that $c$, $c_0$, and $c_{00}$ are subspaces of $\ell_\infty$ (hence equipped with $\ell_\infty$-norm); $c_{00}$ is a dense subspace of $c_{0}$ and its closure is $c_{0}$, $c_0$ is a closed subspace of $c$, and $c$ is a closed subspace of $\ell_\infty$.

Approximation property

One natural follow-up question is this: Does every separable Banach space have a Schauder basis? The answer turns out to be no, and it was proven by Enflo in 1973. This is where it starts:

Theorem 4. Let $X$ and $Y$ be Banach spaces, $(T_n \colon X \to Y)_{n \geq 1}$ be a sequence of finite rank operators, and $T \colon X \to Y$ be an operator such that $\| T_n - T \| \to 0$ as $n \to \infty$. Then $T$ is a compact operator.

Definition. Let $X$ and $Y$ be normed vector spaces. A linear operator $T \colon X \to Y$ is said to be of finite rank if its range is finite-dimensional. And it is called a compact operator if for every bounded sequence $(x_n)_{n \geq 1}$ (i.e. for some constant $C$, $\| x_n \| \leq C$ for all $n$), the sequence $( T x_n )_{n \geq 1}$ has a subsequence that converges in $Y$.

Note that a finite rank operator is clearly compact, and a compact operator is clearly bounded.

Proof of Theorem 4. Let $(x_k)_{k \geq 1} \subseteq X$ be a bounded sequence: there exists $C>0$ such that $\| x_k \| \leq C$ for all $k$. Then,

- Since $T_1$ is compact, there exists a subsequence $(x_{k_1})_{k_1 \geq 1}$ of $(x_k)_{k \geq 1}$ such that $(T_1(x_{k_1}))_{k_1 \geq 1}$ converges in $Y$.

- $T_2$ is also compact, there exists a subsequence $(x_{k_2})_{k_2 \geq 1}$ of $(x_{k_1})_{k_1 \geq 1}$ such that $(T_2(x_{k_2}))_{k_2 \geq 1}$ converges in $Y$.

- $\;\vdots$

- Continuing in this manner: given $T_n$ is finite rank, there exists $(x_{k_n})_{k_n \geq 1}$ a subsequence of $(x_{k_{n-1}})_{k_{n-1} \geq 1}$ such that $\| x_{k_n} \| \leq C$ for all $k_n \geq 1$ and $(T_n(x_{k_n}))_{k_n \geq 1}$ converges in $Y$.

Now we use this to show $(T(y_k))_{k \geq 1}$ is Cauchy in $Y$ and hence $\| y_k \| \leq C$ for all $k$. And since $Y$ is Banach, we will have the subsequence $(T(y_k))_{k \geq 1}$ converges in $Y$. \[ \begin{align*} \| T&(y_k) - T(y_j) \|_Y \\ & = \| T(y_k) - T_n(y_k) + T_n(y_k) - T_n(y_j) + T_n(y_j) - T(y_j) \| \\ & \leq \| (T-T_n)(y_k) \| + \| T_n(y_k - y_j) \| + \| (T_n - T) (y_j) \| \\ & \leq \| T - T_n \| \| y_k \| + \| T_n(y_k - y_j) \| + \| T - T_n \| \| y_j \| \\ & \leq 2C \| T - T_n \| + \| T_n(y_k - y_j) \| \end{align*} \] For given $\varepsilon > 0$, let $n$ be such that $\| T - T_n \| < \frac{\varepsilon}{4c}$ (by hypothesis, we need to have $\| T - T_n \| \to 0$ as $n \to \infty$). But on the other hand, $(T_n(y_n))_{n \geq 1}$ converges in $Y$, and hence is Cauchy; so for given $\varepsilon > 0$, we can take $k$ and $j$ large enough so that $\| T_n y_k - T_n y_j \| < \varepsilon / 2$. All in one: \[ \begin{align*} \| T(y_k) - T(y_j) \| & \leq 2C \| T - T_n \| + \| T_n(y_k - y_j) \| \\ & \leq 2C \frac{\varepsilon}{4C} + \frac{\varepsilon}{2} = \varepsilon \end{align*} \] making $(T(y_k))_{k \geq 1}$ a Cauchy sequence as desired. $\blacksquare$

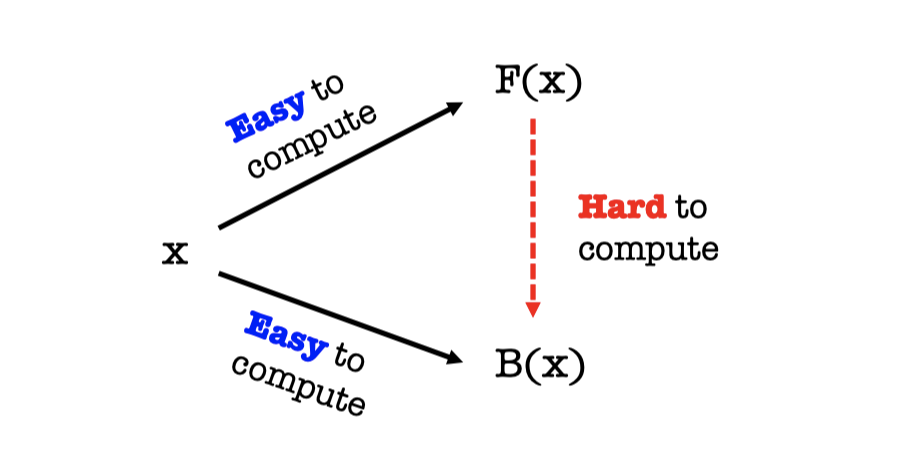

The 'natural question' that we raised before the statement of Theorem 4 is basically asking if the converse of Theorem 4 is true: Let $T$ be a compact operator, can we find a sequence of finite rank operators $(T_n)_{n \geq 1}$ that converges to $T$ (with respect to the norm) always? The answer to this question is in fact true for Hilbert spaces, and also 'seems' to be true for many Banach spaces. For instance, let $X$ be a Banach space and $(e_i)_{i \geq 1}$ be its Schauder basis. Consider $P_n$ the projective operator: \[ x = \sum_{i=1}^\infty a_i e_i \mapsto P_n(x) = \sum_{i=1}^n a_i e_i \] then clearly $P_n$ is finite rank (because $P_n(X)$ is finite dimensional) and $P_n \to P = I_X$ the identity operator (because $P_n(x) \to x$ for all $x \in X$) as $n \to \infty$. This is called the approximation property of Banach space, and in fact, one can prove that a Banach space with a Schauder basis has the approximation property.

Definition. Let $X$ be a Banach space. $X$ is said to have the approximation property if for every compact set $K \subseteq X$ and $\varepsilon > 0$, there exists a finite-rank operator $T$ such that $\| Tx - x\| < \varepsilon$ for all $x \in K$.

Proposition. If a Banach space has a Schauder basis, then it has the approximation property.

However, Enflo gave an explicit construction of a Banach space $X$ such that the identity operator $I_X$ cannot be approximated with other finite (lower) rank operator $T_n$.

Theorem (Enflo). There exists a separable, reflexive Banach space $X$ with a sequence of its finite dimensional subspace $X_n$ such that $\dim(X_n) \to \infty$ as $n \to \infty$, and a constant $C$ such that for all finite rank operator $T$, $\| T - I_X \|$ over $X_n$ (the operator norm with supremum taken over $X_n$) does not converge to $0$ as $n \to \infty$.

This gives two immediate consequences: let $X$ be the Banach space Enflo constructed, then:

(1) $X$ does not have the approximate property, and also does not have a Schauder basis. This is obvious.

(2) The converse of Theorem 4 is not always true. If $I_X$ can be approximated then any compact operator $T$ can be approximated (by composing each approximation of $I_X$ with $T$). Additionally, if $X$ is separable and reflexive then the other direction also holds (this is a result by Grothendieck, according to Enflo's paper). Enflo's Banach space is separable and reflexive, and hence it serves as the counterexample to the converse of Theorem 4.

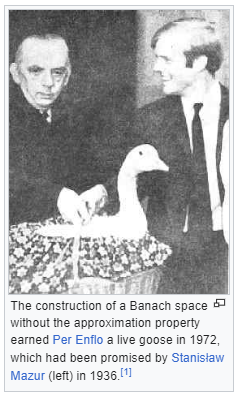

For his contribution, Enflo was awarded a live goose from Mazur. This story is outlined pretty well in this Wikipedia page for Enflo.

Enflo solved Mazur's problem and earned a goose.

I solved my own, and became the goose.

I wonder what it'd take someone to win a FlaggnGoose (smirk).

(FlaggnGoose is my username for CTF competitions.)

Updated: