Kővári-Sós-Turán Theorem

Published:

I came across this theorem when my labmates and I together were trying to generalize results in [Block et al. ITC’ 21] written by my advisor (+ Simina and others), and it has then been my favorite theorem in extremal graph theory ever since. The proof involves double counting, which is a pretty standard technique in math olympiad. It was interesting to see how an olympiad-y technique can lead to a huge result that marked the beginning of a whole field in mathematics!

Although I am not an extremal combinatorialist, I am a fan of this theorem enough to write a blogpost about it. I will also outline its application to communication complexity lower bound (also cryptography, but will not be discussed here) that was discovered fairly recently (see Further Readings).

Turán’s Problem

Extremal combinatorics is essentially concerned with questions of the following form: how complex can a system be, given certain constraints? Substituting graph-theoretic contexts into this question (say, system = graph, complexity = density of edges, and constraints = patterns):

Problem (Turán-Type Problem). Let $n \in \mathbb{N}$ and $H$ a graph. Define the Turán number of a graph $H$ to be $$ \mathrm{ex}(n,H) := \max\{ |E| : G = (V,E) \text{ s.t. } |V| = n \text{ and } G \text{ is } H\text{-free} \} $$ What is $\mathrm{ex}(n, H)$?

This quantity and problem are named after Turán (obviously), in particular it is named after his theorem:

Theorem (Turán). Let $K_r$ be the complete graph on $r$ vertices. Then, $$ \mathrm{ex}(n, K_{r+1}) = \left( 1 - \frac{1}{r} + o(1) \right)\frac{n^2}{2} $$

Bounds

This is quite a complicated problem, let us start with a simple case: triangle ($K_3$) free graphs. Clearly, you can have a bipartite graph: no matter how many edges it has, it will always be triangle-free. So, given $n$ vertices, you can draw a complete bipartite graph $K_{s,t}$ where $s+t=n$ and it will be triangle-free. Because $K_{s,t}$ has $st$ many edges, we can maximize this: it is maximized when $s = \lfloor n/2 \rfloor$ and $t = \lceil n/2 \rceil$, and hence

\[\mathrm{ex}(n, K_3) \geq \left\lfloor \frac{n}{2} \right\rfloor \left\lceil \frac{n}{2} \right\rceil = \left\lfloor \frac{n^2}{4} \right\rfloor\]And it turns out that this is in fact the most optimal value.

Theorem (Mantel). For all $n \in \mathbb{N}$, $ \mathrm{ex}(n, K_3) = \lfloor n/2 \rfloor \lceil n/2 \rceil$.

Clearly Mantel’s theorem is a special case of Turán’s theorem when $r = 2$.

Proof of Mantel’s Theorem. It suffices to prove that a $K_3$-free graph $G = (V,E)$ with $\lvert V \rvert = n$ has $\lvert E \rvert \leq n^2/4$.

Let $x, y \in V$ such that $(x,y) \in E$. Clearly $x$ and $y$ do not share any adjacent node (neighbors), because they did, called $z \in V$, then $x$,$y$,$z$ would form a triangle which is $K_3$. So, if we let $N(x)$ be the set of nodes adjacent to $x \in V$, then $\lvert N(x) \rvert = \deg(x)$ by definition and

\[\lvert N(x) \cup N(y) \rvert = \lvert N(x) \rvert + \lvert N(y) \rvert = \deg(x) + \deg(y)\]Summing this quantity up over all $(x,y) \in E$, we have

\[\begin{align*} \sum_{(x,y) \in E} (\deg(x) + \deg(y)) & = \sum_{(x,y) \in E} \deg(x) + \sum_{(x,y) \in E} \deg(y) \\ & = \frac{1}{2} \sum_{x \in V} \sum_{y \in N(x)} \deg(x) + \frac{1}{2} \sum_{y \in V} \sum_{x \in N(y)} \deg(y) \\ & = \frac{1}{2} \sum_{x \in V} \deg(x) \sum_{y \in N(x)} 1 + \frac{1}{2} \sum_{y \in V} \deg(y) \sum_{x \in N(y)} 1 \\ & = \frac{1}{2} \sum_{x \in V} \deg(x)^2 + \frac{1}{2} \sum_{y \in V} \deg(y)^2 \\ & = \sum_{v \in V} \deg(v)^2 \\ & \geq \frac{1}{|V|} \left( \sum_{v\in V} \deg(v) \right)^2 && \hspace{-6cm} (\because \textsf{Cauchy-Schwarz}) \\ & = \frac{1}{n} (2 |E|)^2 = \frac{4|E|^2}{n} && \hspace{-6cm} (\because \textsf{Handshaking Lemma}) \end{align*}\]But notice that we must have $\lvert N(x) \cup N(y) \rvert \leq \lvert V \rvert$ trivially, because otherwise it implies that the graph has more than $\lvert V \rvert$ vertices just around $x$ and $y$ which does not make sense. Therefore, all in one:

\[\sum_{(x,y) \in E} |V| = n|E| \geq \frac{4|E|^2}{n} \implies |E| \leq \frac{n^2}{4}\]which completes the proof. $\blacksquare$

As mentioned, Mantel’s theorem is a special case of Turán’s theorem, so we will prove Turán’s theorem similar to how Mantel’s theorem was proven, but also not that similar. Our goal would be to prove that

\[\mathrm{ex}(n, K_{r+1}) = \left( 1 - \frac{1}{r} + o(1) \right)\frac{n^2}{2}\]Note that $n^2/2$ is approximately the number of maximum edges that a graph with $n$ vertices can have. Basically what this quantity says is that we can have as many edges as we can, as long as we exclude around $1/r$-portion of them. So, one way to describe Turán’s theorem in plain english would be: if a graph is “globally dense” (close to having full edges) then it is also “locally dense” (contains a complete subgraph). Where the asymptotics part $o(1)$ in this quantity came from is yet unclear, so for now let us prove the following version of Turán’s theorem:

\[\mathrm{ex}(n, K_{r+1}) \leq \left( 1 - \frac{1}{r} \right)\frac{n^2}{2}\]Proof of Turán’s Theorem. We will use strong induction on $n$.

- (Base Case) Let us prove that the statement holds for $n \leq r$. This is obvious, intuitively and algebraically: $$ |E| \leq \binom{n}{2} = \frac{n(n-1)}{2} = \left( 1 - \frac{1}{n} \right) \frac{n^2}{2} \leq \left( 1 - \frac{1}{r} \right) \frac{n^2}{2} $$

- (Inductive Hypothesis) Suppose that the statement is true up to $n = k - 1$ where $k > r$.

- (Inductive Step) Consider a $K_{r+1}$-free graph $G$ with $n = k > r$ nodes and maximal edges. It is safe to assume that this graph has $K_r$ in it, because otherwise we can add more edges ($K_r$ obviously is a subgraph of $K_{r+1}$). Let $A$ be a $K_r$ in $G$.

- $A$ contains $r$ vertices and $\binom{r}{2}$ edges indeed.

- By inductive hypothesis, $G\setminus A$ contains $\leq \left( 1 - \frac{1}{r} \right)\frac{(n-r)^2}{2}$ edges.

- There can be no more than $(r-1)(n-r)$ edges between $A$ and $G\setminus A$ for sure. $A$ has $r$ vertices, but every $v \in G\setminus A$ can be adjacent to at most $r-1$ vertices in $A$ because otherwise it could induce a $K_{r+1}$ which $G$ does not have.

Adding them all up, we have: $$ \begin{align*} |E(G)| & \leq \binom{r}{2} + \left( 1 - \frac{1}{r} \right)\frac{(n-r)^2}{2} + (r-1)(n-r) \\ & = \frac{n^2}{2} - \frac{n^2}{2r} = \left( 1 - \frac{1}{r} \right)\frac{n^2}{2} \end{align*} $$ as desired. $\blacksquare$

Extremals

In this section, for handwavying purposes, I will omit floors and ceilings until it is necessary for context and intuitions. Handwavying is a way of life ![]()

The proof of Mantel’s theorem (also Turan’s theorem) we discussed above gives us information on extreme values, but it does not give us any description of how to construct such a graph (what they look like) that has the maximum possible number of edges. More specifically, we know that $K_{n/2, n/2}$ does achieve $|E| = \mathrm{ex}(n, K_{3})$, but the proof did not quite have any sign of $K_{n/2, n/2}$. This begs a new question: are there any other triangle-free graphs (with the same number of edges) other than $K_{n/2, n/2}$ that has $|E| = \mathrm{ex}(n, K_{3})$?

Before giving an answer to this, let us take a look at another proof of Mantel’s theorem. The core idea is more or less the same.

Alternative Proof of Mantel’s Theorem. Let $G = (V,E)$ be a $n$-vertex triangle-free graph. Because $G$ is triangle-free, for any $x \in V$, its neighbors $N(x)$ must form an independent set; otherwise, there is an edge going from one vertex of $N(x)$ to another of $N(x)$, which will then form a triangle with $x$. (Recall that an independent set is a collection of vertices where no two vertices within the set are connected.)

Let $A$ be a largest independent set of $G$. Clearly, $\deg(x) \leq \lvert A \rvert$, and also $A$ should contain any independent set of $G$ by the property of independent set, i.e. $N(x) \subseteq A$.

Note that, if we were to partition $G$ into $A$ and $G\setminus A$, then every edge $e \in E$ must be either between $A$ and $G\setminus A$ or entirely within $G\setminus A$; it cannot be within $A$ because $A$ is an independent set. So we have:

\[\begin{align*} |E| \leq |E| + |E(G \setminus A)| & = \sum_{v \in G \setminus A} \deg(v) \\ & \leq \sum_{v \in G \setminus A} |A| = |A| |G\setminus A| && (\because \deg(v) \leq |A| ) \\ & \leq \left( \frac{|A| + |G\setminus A|}{2} \right)^2 = \frac{n^2}{4} && (\because \textsf{AM-GM}) \end{align*}\]as desired. $\blacksquare$

This proves Mantel’s theorem of course, but let us pay attention to the inequalities that we used.

In $\lvert E\rvert \leq \lvert E \rvert + \lvert E(G \setminus A) \rvert$, the equality holds iff there is no edge in $G \setminus A$.

In $\deg(v) \leq \lvert A \rvert$, the equality holds iff every vertex in $G\setminus A$ is complete to $A$.

In AM-GM, the equality holds iff $\lvert A \rvert = \lvert G\setminus A\rvert$.

These exactly comprise the definition of complete bipartite graph $K_{n/2, n/2}$!

If your intuition says we would need a complete tripartite graph $K_{n/3, n/3, n/3}$ for $K_4$-free graphs, and more generally a complete $r$-partite graph $K_{n/r, \dots, n/r}$ for $K_{r+1}$-free graphs, then congratulations - you have a keen observation :-) But of course, because $n$ might not be divisible by $r$, we need to be a little bit careful. This is where Turán graphs kick in.

Definition (Turán Graph). A Turan graph $T_{n,r}$ is a complete multipartite graph of $n$ vertices and $r$ partites, where each partite has either the same number of vertices or differ by at most one. Its number of edges is denoted $t(n,r)$.

Here is a very famous example: $T_{13,4}$ (famous for appearing at the top of the Wikipedia page on Turán graph).

If $n$ is divisible by $r$. Then we can compute $t(n,r)$ very easily:

\[t(n,r) = \binom{r}{2} \left( \frac{n}{r} \right)^2 = \left( 1 - \frac{1}{r} \right) \frac{n^2}{2}\]This is exactly the upper bound that we derived in our proof! Now, what happens if $n$ is not divisible by $r$? Let $n = kr + r’$ where $0<r’<r$. Then $n-r’$ is divisible by $r$ for sure. $T_{n,r}$ would be a complete $r$-partite graph with $r’$ many partites with size $n+1$ and $r-r’$ many partites with size $n$. A more ‘constructive’ way to put it would be: $T_{n,r}$ is basically $T_{n-r’, r}$ with $r’$ extra vertices. Each of $r’$ vertices will first generate $\left(1 - \frac{1}{r}\right) (n-r’)$ edges with the nodes in $T_{n-r’,r}$. They will then generate $\binom{r’}{2}$ edges among themselves. Hence,

\[\begin{align*} t(n,r) & = t(n-r', r) + r' \left(1 - \frac{1}{r}\right) (n-r') + \binom{r'}{2} \\ & = \left( 1 - \frac{1}{r} \right) \frac{(n-r')^2}{2} + \left( 1 - \frac{1}{r} \right) r'(n-r') + \binom{r'}{2} \\ & = \left( 1 - \frac{1}{r} \right) \frac{(n-r')}{2} \left( (n-r') + 2r' \right) + \binom{r'}{2} \\ & = \left( 1 - \frac{1}{r} \right) \frac{n^2}{2} - \left( 1 - \frac{1}{r} \right) \frac{r'^2}{2} + \binom{r'}{2} \\ & = \left( 1 - \frac{1}{r} \right) \frac{n^2}{2} - \frac{r'(r-r')}{2r} \end{align*}\]Hence, now we see the source of the asymptotic variable $o(1)$ in the statement of Turán’s theorem.

\[\left( 1 - \frac{1}{r} \right) \frac{n^2}{2} - \frac{r}{8} \leq t(n,r) \leq \left( 1 - \frac{1}{r} \right) \frac{n^2}{2}\]In any case, we now have the following:

Theorem (Turán: Version 2). Every $K_{r+1}$-free graph with $n$ vertices that has the maximal number of edges $\mathrm{ex}(n, K_{r+1})$ is a $T_{r,n}$, i.e. $\mathrm{ex}(n, K_{r+1}) \leq t(n,r)$.

This theorem follows directly from the proof of Turán’s theorem version 1 and the fact that $T_{r,n}$ has the most number of edges among all complete $r$-partite graphs with $n$ nodes which is obvious. For readers seeking a full proof: there are many sources out there, I recommend [Ch. 7, Diestel]. So, here we will discuss an alternative proof that involves a different technique.

Proof of Turán’s Theorem v2. Let $G = (V,E)$ be the maximal $K_{r+1}$-free graph with $n$ vertices.

For points $x,y,z\in V$, if $(x,y) \notin E$ and $(y,z)\notin E$ then $(x,z)\notin E$. To see this, suppose not: let $(x,y) \notin E$ and $(y,z)\notin E$ but $(x,z)\in E$. If we had $\deg(y) < \deg(x)$, then one can replace $y$ with $x’$ such that $N(x) = N(x’)$, then this is still a $K_{r+1}$-free graph (because if it is not then the original graph $G$ should not have been $K_{r+1}$-free in the first place) yet has more edges than $G$. This contradicts the maximality of $G$, and hence it must be the case that

If we replace $x$ and $z$ with $y’$ like we did before, then we again should get a $K_{r+1}$-free graph by the same reasoning, but this again increases the number of edges, again contradicting the maximality.

Basically this suggests that $G$ must be a multipartite graph with $\leq r$ parts. We can have it to be a complete multipartite graph to maximize the number of edges. To optimize even further, we can have each part to have vertices not more or less by $> 1$ than the other, because otherwise moving a vertex from a larger part to the smaller can increase the number of edges. This exactly corresponds to the Turan graph $T_{r,n}$. $\blacksquare$

I initially advertised this proof as a proof that uses a different technique, but one might have noted already that the core idea is similar to the first proof of Mantel’s theorem.

Generalizations

One thing you might have noticed from the Turán graph $T_{r,n}$ is that it is $r$-colorable, and any graph that requires more than $r$ colors will not exist within $T_{r,n}$, hence the following generalization:

Theorem (Erdős, Simonovits '66). For $\chi(H) \geq 2$ where $\chi$ denotes the chromatic number, $$ \mathrm{ex}(n, H) = \left( 1 - \frac{1}{\chi(H) - 1} + o(1) \right) \frac{n^2}{2} $$

This theorem is called the fundamental theorem of extremal graph theory. To prove this, we need to use Erdős-Stone theorem:

Theorem (Erdős, Stone '46). For all $n$, $\mathrm{ex}(n, T_{r, rs}) = t_{r-1}(n) + o(n^2)$.

Here, don’t get distracted by another Turán graph $T_{r,rs}$; think of it as a complete $r$-partite graph where each partition consists of exactly $s$ vertices. The proof of this theorem requires the use of Szemerédi regularity lemma (I heard there is an elementary proof, but I personally do not know), and hence will not be covered in this post.

Proof of Erdős-Simonovits Theorem. Let $r = \chi(H)$. On one hand, $H$ is not a subgraph of $T_{r-1,n}$ for all $n$ as discussed, so $\mathrm{ex}(n,H) \geq t(n, r-1)$. On the other hand, clearly $H$ is a subgraph of complete $r$-partite graph of $r \lvert V(H) \rvert$ vertices, i.e. $T_{r, rs}$ where $s = \lvert V(H) \rvert$, and so

\[\mathrm{ex}(n,H) \leq \mathrm{ex}(n, T_{r,rs}) = t_{r-1}(n) + o(n^2)\]by Erdős-Stone theorem. $\blacksquare$

Clearly, both $K_{r,s}$ and $T_{r, rs}$ have chromatic number $r$. Erdős-Simonovits Theorem is essentially a generalization of Erdős-Stone Theorem, and because of this, Erdős-Simonovits Theorem is often referred to as Erdős-Stone or Erdős-Stone-Simonovits Theorem.

One thing to note here is that if $H$ is bipartite, both theorems say $\mathrm{ex}(n,H) = o(n^2)$ (note $\chi(H) = 2$). But, this does not seem like a good bound, at least for small $n$’s. For example, when $H = K_{2,2}$:

Theorem (Reiman '58; Erdős, Sós, Rényi '63). $\mathrm{ex}(n, K_{2,2}) = \Theta(n^{3/2})$.

Reiman proved the upper bound, and Erdős, Sós, and Rényi proved the lower bound. The lower bound proof involves some elementary additive combinatorics which I find it interesting!

Proof (Sketch). For upper bound, note first that $\mathrm{ex}(n, K_{2,2}) = \mathrm{ex}(n, C_4)$. Let $G = (V,E)$ and $\lvert V \rvert = n$. Let $S$ be the set of all vertices $v$ pairs with its two neighbors $u_1, u_2$ unordered. Clearly, for each vertex $v$, there are $\binom{\deg(v)}{2}$ many unordered pair $(u_1, u_2)$, so $\sum_{v\in V} \binom{\deg(v)}{2}$ should be the cardinality of $S$. But note that this should not exceed the number of edges of $G$. This is because, $u_1$ and $u_2$ cannot have more than one common neighbor, as otherwise they will form $C_4$. Hence,

\[|S| = \sum_{v\in V} \binom{\deg(v)}{2} \leq |E| = \binom{n}{2}\]Then by Cauchy-Schwarz and the basic fact that $\lvert E \rvert = \sum_{v \in V} \deg(v)$,

\[\begin{align*} & \sum_{v\in V} \binom{\deg(v)}{2} \leq \binom{n}{2} \\ & \implies \sum_{v \in V} \deg(v)^2 \leq n(n-1) + \sum_{v \in V} \deg(v) \\ & \implies \left( \sum_{v \in V} \deg(v) \right)^2 \leq n \sum_{v \in V} \deg(v)^2 \leq n^2(n-1) + n \sum_{v \in V} \deg(v) \\ & \implies (2|E|)^2 \leq n^2(n-1) + n |E| \\ & \implies |E| \leq \frac{n}{4}(1 + \sqrt{4n-3}) \implies |E| = O(n^{3/2}) \end{align*}\]We shall show that this bound is tight by construction. Let $p$ be a prime number (or a prime power) and construct $G = (V,E)$ to be such that $V = \mathbb{F}_p^\times \times \mathbb{F}_p$, and for each $(a,b) \in V$ and $(c,d) \in V$,

\[((a,b), (c,d)) \in E \iff ac = b+d\]Then $n = \lvert V \rvert = p(p-1)$ whereas $\lvert E \rvert = n(p-1)/2$ because for each $(a,b) \in V$ there are $p-1$ solutions $(x,y)$ to the equation $ax = b+y$. This graph is clearly $C_4$-free, because the system of solution

\[\begin{cases} ax = b + y \\ cx = d + y \end{cases}\]can have only up to one solution by Bézout’s theorem which, when $a \neq c$ and $b \neq d$, it is

\[(x,y) = \left( \frac{b-d}{a-c}, \frac{x(a+c) - (b+d)}{2} \right)\]That is, $(a,b)$ and $(c,d)$ only shares up to one neighbor together, making it $C_4$-free. $\blacksquare$

There is also a result for $K_{3,3}$, which I don’t feel like proving here:

Theorem (Brown '66; Füredi '96). $\mathrm{ex}(n, K_{3,3}) = \Theta(n^{5/3})$.

This sure sparks a new question. Will $n^2$ be a tight bound for $K_{s,t}$-free graphs if $s,t$ get large? Or will it be of the form $n^{2 - 1/s}$ (or $t$ instead?) just like these two base cases $K_{2,2}$ and $K_{3,3}$ suggest?

Zarankiewicz Problem

Zarankiewicz posed a question similar in form to Turán’s question, except he restricted to the settings of bipartite graphs.

Problem (Zarankiewicz). Let $G = (L,R,E)$ be a $K_{s,t}$-free bipartite graph such that $|L| = \ell$ and $|R| = r$. The Zarankiewicz function $z(\ell,r;s,t) := \mathrm{ex}(\ell,r;K_{s,t})$ denotes the maximum possible number of edges in $G$.

But of course, we do not need to restrict our graph $G$ to be a bipartite graph: for $G = (V,E)$ with $\lvert V \rvert = n$, we can study $z(n;s,t) := \mathrm{ex}(n; K_{s,t})$ instead.

It turns out Zarankiewicz’s problem in general is very difficult. Currently, the best result is this result by Alon, Kollar, Rónyai, and Szabó:

Theorem (Kollar, Rónyai, Szabó '96; Alon, Rónyai, Sazbó '99). If $t \geq (s-1)! + 1$ then $\mathrm{ex}(n, K_{s,t}) = \Theta(n^{2 - 1/s})$.

This is an extension of known base cases $\mathrm{ex}(n, K_{2,2}) = \Theta(n^{3/2})$ and $\mathrm{ex}(n, K_{3,3}) = \Theta(n^{5/3})$ that we saw in the previous section. Whether this result holds for all parameters or not is still unknown; evidently, we do not even how to approximate $\mathrm{ex}(n, K_{4,4})$ tightly yet!

There are cases where Zarankiewicz’s function can be computed exactly, one being the following result by Culik:

Theorem (Culik '56). If $s,t,$ and $\ell$ are fixed, then for all $r > (t-1) \binom{\ell}{s}$, $$ z(\ell,r;s,t) = (s-1)r + (t-1)\binom{\ell}{s} $$

Not many results are known in Zarankiewicz’s Problem. Currently the most ‘well-established’ result that works for all parameters is Kővári-Sós-Turán Theorem.

Kővári-Sós-Turán Theorem

Theorem (Kővári, Sós, Turán '54). Let $G = (L,R,E)$ be a $K_{s,t}$-free bipartite graph such that $\lvert L \rvert = n$ and $\lvert R \rvert = m$. Then, $$ z(n,m;s,t) \leq n(t-1)^{\frac{1}{s}} m^{1 - \frac{1}{s}} + (s-1)m $$ In other words, $z(n,m;s,t) = O(nm^{1-\frac{1}{s}} + m)$.

This should explain the mysterious asymptotics of the form $\Theta(n^{2 - 1/s})$ in the known results. The proof idea, in my perspective, is similar to the proof of Turán’s theorem. Instead of couting and dealing with $\deg(x)$ for $x \in V$, we count the number of stars: $x$ and its neighboring nodes. The difference here is that we fix the size of the star, but we fix it to the maximum possible value. Let us see what all of these mean.

Proof of Kővári-Sós-Turán Theorem. Clearly $t \leq m$ and $s\leq n$ because if not then $G$ would naturally be a $K_{s,t}$-free graph, regardless of how many edges it has. WLOG let $s \geq 2$ and $S$ be the number of stars $K_{s,1}$ in $G$.

- (Upper Bound) We shall count $K_{s,1}$'s by forming them from $L$.

- A $K_{s,1}$ in $G$ would consist of $s$ vertices in $L$ and one vertex in $R$ that all $s$ vertices in $L$ are connected to. Let $L_s \subseteq L$ such that $\lvert L_s \rvert = s$, and $R_{L_s} \subseteq R$ be the set of vertices in $R$ that are adjacent to every vertex in $L_s$. Then $\lvert R_{L_s} \rvert \leq t-1$ because otherwise $L_s$ and $R_{L_s}$ would form a $K_{s,t}$. Hence, $L_s$ has at most $t-1$ different vertices that they can choose to form a $K_{s,1}$, and there are $\binom{n}{s}$ ways to form such an $L_s$. Hence, $$ S \leq \binom{n}{s} (t-1) = \frac{n(n-1)\cdots(n-s+1)}{s!} (t-1) \leq \frac{n^s}{s!}(t-1) $$

- (Lower Bound) We shall count $K_{s,1}$'s by forming them from $R$.

- Given $v \in R$, if $\deg(v) < s$ then there cannot exist a $K_{s,1}$ that contains $v$. If $\deg(v) \geq s$, then we can form a $K_{s,1}$ by choosing $s$ vertices out of $d_v$ vertices in $L$ that $v$ is connected to. Hence (denote $d_v := \deg(v)$ for brevity), $$ S = \sum_{\substack{v \in R \\ \deg(v) \geq s}} \binom{\deg(v)}{s} = \sum_{\substack{v \in R \\ d_v \geq s}} \frac{d_v(d_v-1)\cdots(d_v-s+1)}{s!} \geq \sum_{\substack{v \in R \\ d_v \geq s}} \frac{(d_v-s+1)^s}{s!} $$ As mentioned, really all we need is the case where $d_v \geq s$. So, define a function $f \colon \mathbb{R} \to \mathbb{R}_{\geq 0}$ such that $$ f(x) = \begin{cases} (x-s+1)^s / s! & \text{if } x \geq s \\ 0 & \text{otherwise} \end{cases} $$ so that we can rewrite the above inequality as $$ S \geq \sum_{\substack{v \in R \\ d_v \geq s}} \frac{(d_v-s+1)^s}{s!} = \sum_{\substack{v \in R \\ d_v \geq s}} \frac{(d_v-s+1)^s}{s!} + \sum_{\substack{v \in R \\ d_v \leq s-1}} 0 = \sum_{v\in R} f(d_v) $$ Note that $f$ is a convex function. So we can lower bound the sum using Jensen's inequality as follows: $$ \begin{align*} \frac{1}{\lvert R \rvert} \sum_{v \in R} f(d_v) & = \sum_{v \in R} \frac{f(d_v)}{m} && (\because m = \lvert R \rvert) \\ & \geq f\left( \sum_{v \in R} \frac{d_v}{m} \right) && (\because \textsf{Jensen's inequality})\\ & = f\left( \frac{\sum_{v \in R} d_v}{m} \right) = f\left( \frac{\lvert E \rvert}{m} \right) && (\because G \textsf{ is bipartite})\\ & = \frac{1}{s!} \left( \frac{\lvert E \rvert}{m} - s + 1 \right)^s \end{align*} $$ and hence, $$ S \geq \sum_{v \in R} f(d_v) \geq \frac{m}{s!} \left( \frac{\lvert E \rvert}{m} - s + 1 \right)^s $$

All in one, $S$ is upper and lower bounded as

\[\frac{m}{s!} \left( \frac{\lvert E \rvert}{m} - s + 1 \right)^s \leq S \leq \frac{n^s}{s!}(t-1)\]which we can solve for $\lvert E \rvert$:

\[\frac{m}{s!} \left( \frac{\lvert E \rvert}{m} - s + 1 \right)^s \leq \frac{n^s}{s!}(t-1) \implies \lvert E \rvert \leq n(t-1)^{\frac{1}{s}} m^{1 - \frac{1}{s}} + (s-1)m\]as desired. $\blacksquare$

As hinted, the base graph does not have to be a bipartite graph.

Theorem (Kővári, Sós, Turán '54: Version 2). For natural numbers $s$ and $t$ where $s \leq t$, $$ \mathrm{ex}(n, K_{s,t}) \leq \frac{1}{2}(t-1)^{\frac{1}{s}} n^{2 - \frac{1}{s}} + \frac{1}{2} (s-1)n $$ In other words, $\mathrm{ex}(n, K_{s,t}) = O(n^{2-\frac{1}{s}})$.

The proof is more or less the same.

It is conjectured that the bound induced by Kővári-Sós-Turán Theorem is tight up to a constant factor. Using the power of randomized constructions (Erdős-Rényi graphs), one can prove a lower bound that seems asymptotically close to Kővári-Sós-Turán Theorem.

Theorem. Let $G = (V,E)$ be a graph. There exists a positive constant $C_G$ such that for all $n \geq 2$, $$ \mathrm{ex}(n, G) \geq C_G~n^{2 - \frac{\lvert V \rvert-2}{\lvert E \rvert - 1}} $$ and hence, $\mathrm{ex}(n, K_{s,t}) = \Omega\left(n^{2 - \frac{s+t-2}{st-1}} \right)$.

Even though $\lim_{t \to \infty} \frac{s+t-2}{st-1} = \frac{1}{s}$, this does not resolve the conjecture because it is not for all $t$.

Connections to CS

These might merely be a bunch of random fun facts in graph theory to some people, but it turns out they have some connections to information theory, in particular communication complexity. I will try to communicate what communication complexity theory is, using as less communication complexity theory as possible in the least complex way I can do (pun intended). I am also not an expert in this field anyway.

Communication complexity

Let $G = (L,R,E)$ be a bipartite graph with nodes $\lvert L \rvert = \lvert R \rvert = n$. Adjacencies of this bipartite graph can be represented with a $n$-by-$n$ binary matrix $M$:

\[M_{i,j} =: M(i,j) =: \begin{cases} 1 & \text{if } (i,j) \in E \text{ where } i \in L, j \in R \\ 0 & \text{otherwise} \end{cases}\]For convenience, we will call this matrix $M$ the adjacency matrix of $G$. A complete bipartite graph (hereafter biclique) will be a rectangle of all $1$’s (monochromatic rectangle), up to some permutations of row and column; more mathematically, it is a rank-$1$ matrix.

This is in fact how a communication problem in theoretical computer science is defined. Given a binary matrix $M_{a,b}$, with Alice being the owner of rows ($a$’s) and Bob the owner of columns ($b$’s), they can communicate and collaboratively compute the value of $M(a,b) = M_{a,b}$. If, for instance, $M$ has rank $1$ as mentioned, then Alice can simply send whether $a$ is one of the rows that consists of the rectangle of $1$’s or not, which then Bob can compute $M(a,b)$ based on the column $b$. Hence, the function $M(a,b)$ is computable with just $1$ bit of communication.

As you might have guessed, this can indeed be generalized.

Theorem (Mehlhorn, Schmidt '82). Let $M$ be a rank-$r$ matrix. There exists a deterministic two-party protocol that computes $M(a,b) := M_{a,b}$ with $D(M) = r + 1$ bits of communications. In particular, $$ \log(r) \leq D(M) \leq r + 1 $$ We call $D(M)$ the (deterministic) communication complexity of $M$.

Basically $D(M)$ is the minimum number of bits of communications required to compute $M(a,b)$; note that $D(M) \leq \lambda$ where $a,b \in {0,1}^\lambda$ is obvious: Alice can simply send Bob her value $a$ and have Bob compute $M(a,b)$ himself, or the other way around.

This is also where the infamous log-rank conjecture comes from.

Conjecture (Log-rank Conjecture). For $M$ with rank $r$, $\log(r) \leq D(M) \leq \mathrm{poly}(\log(r))$.

Currently the best upper bound is $D(M) = O(\sqrt{r})$, found by Sudakov and Tomon.

Because a rectangle of $1$’s is a rank-$1$ matrix, you might have intuitively noticed by now that the rank of the matrix has a close relationship with the number of rectangles you need to partition or cover the matrix. A rectangle is a biclique (complete bipartite graph), and hence they are called biclique partition and cover number, denoted $\mathrm{bp}$ and $\mathrm{bc}$ respectively.

Theorem (Gregory et al. '91). Let $M$ be a binary matrix, then $$ \mathrm{rank}_{0/1}(M) = \mathrm{bp}(M) \geq \mathrm{rank}_+(M) = \mathrm{bc}(M) $$ where $\mathrm{rank}_{0/1}(M)$ denotes the binary rank of $M$ where additions are over $\mathbb{Z}$ (i.e. integer addition) and $\mathrm{rank}_{+}(M)$ denotes the nonnegative (Boolean) rank where the addition is defined as the element-wise maximum (i.e. $x+y = \max(x,y)$).

In paricular, the biclique cover number $\mathrm{bc}(M)$ precisely captures the nondeterministic communication complexity $N(M)$. Nondeterministic protocol for $M$ is the deterministic protocol for $M$ where Alice and Bob has access to a common advise string $\pi$ generated by an oracle that has access to both Alice’s and Bob’s inputs. If $M(a,b) = 0$ then the protocol should return $0$ as intended, regardless of the advise $\pi$; if $M(a,b) = 1$ then there exists $\pi$ such that the protocol returns $1$ (hence the ‘nondeterminism’!).

Theorem. $N(M) = \log(\mathrm{bc}(M))$ for all binary matrix $M$.

A communication from one to the other corresponds to partitioning the matrix $M$ into two parts either horizontally or vertically (depending on who is sending the bit), and in the end the matrix is partitioned into monochromatic rectangles. Because $c$ bits of communication would generate $2^c$ rectangles (note however that the process of partitioning to monochromatic rectangles does not always correspond to a protocol),

Theorem. $D(M) \geq \log(\mathrm{bp}(M))$ for all binary matrix $M$.

Given these, it is natural to think that Zarankiewicz problem and communication complexity theory have connections, in the sense that the former asks the maximum number of $1$’s in a matrix that does not contain a rectangle of certain size.

P4-free Bipartite Graphs

From the results and examples above, one would’ve had correctly guessed that the equality function $\mathrm{EQ}(x,y)$ is an example of functions that have high communication complexity.

\[\mathrm{EQ}(x,y) = \begin{cases} 1 & \text{if } x = y \\ 0 & \text{otherwise} \end{cases}\]In particular, its rank is $\lambda$ (it is an identity matrix) and it requires $\lambda + 1$ bits of communications (where $x,y \in \left\{0,1\right\}^\lambda$) in deterministic protocol. But even with the power of nondeterminism, the communication complexity of the equality function $\mathrm{EQ}(x,y)$ is very high because, roughly speaking, you still need to show that all $\lambda$ bits match to verify $x = y$.

This then begs a new question: when computing a two-party function $f(x,y)$, would having an equality oracle give any advantage?

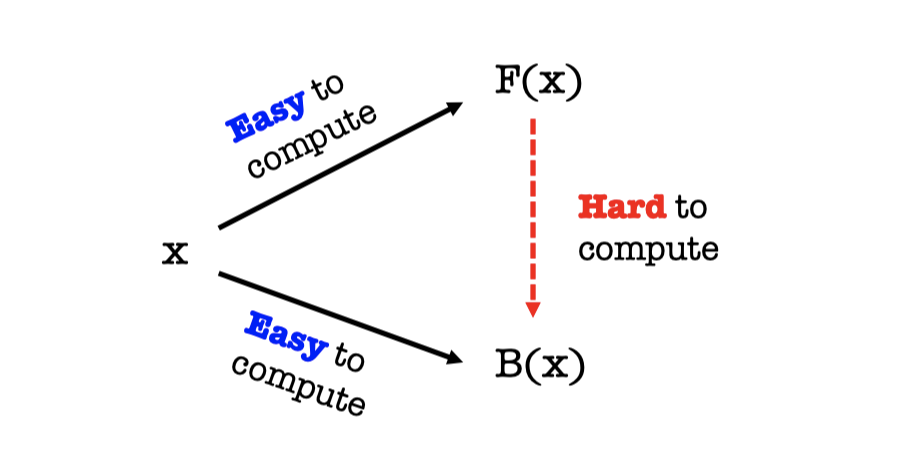

Definition. A nondeterministic protocol for $M$ relative to $\mathrm{EQ}$ oracle is a pair of functions $A$ and $B$ such that:

1. For all $(a,b)$ s.t. $M(a,b) = 1$, there exists $\pi$ such that $\mathrm{EQ}( A(a, \pi) , B(b, \pi) ) = 1$.

2. If $(a,b)$ gives $M(a,b) = 0$, then for all $\pi$, we have $\mathrm{EQ}( A(a,\pi), B(b,\pi)) = 0$.

The communication complexity of this protocol is the minimum possible length of $\pi$, and is denoted $\mathsf{NP}^{\mathsf{EQ}_{\mathsf{cc}}}(M)$.

$A(a,\pi)$ is basically the ‘preprocessing’ function that Alice computes based on its input $a$ and the advise $\pi$, and the same for $B(b, \pi)$.

Let us introduce our new object of interest.

Definition ($P_4$-free Bipartite Graph). We say a bipartite graph $G = (L,R,E)$ is $P_4$-free if no four vertices of $G$ induce a $P_4$ subgraph.

This does not look very interesting, and I hope you agree. But it has a very interesting property, which I also hope you agree.

Proposition. A bipartite graph $G = (L,R,E)$ is $P_4$-free iff it is a vertex-disjoint union of bicliques, i.e. each connected component is a biclique. More precisely, there exists disjoint $L_1, L_2, \dots, L_n \subseteq L$ and disjoint $R_1, R_2, \dots, R_n \subseteq R$ such that $E = \bigcup_{i=1}^n (L_i \times R_i)$.

The key observation here is that a biclique is $P_4$-free itself. And if we represent a $P_4$-free graph $G$ as a matrix $M$, then it would be a disjoint union of rectangles of $1$’s.

If $G$ is $P_4$-free, then Alice and Bob can compute the function $M(a,b)$ with one oracle call to the equality $\mathrm{EQ}$, without the nondeterministic input (advise) $\pi$: Alice and Bob can compute the connected component corresponding to their inputs $a$ and $b$, namely $C_a = L_a \times R_{(…)}$ and $C_b = L_{(…)} \times R_b$ respectively, then call $\mathrm{EQ}(C_a, C_b)$. The other direction also holds as well. We will use this as a base case.

Now, consider a function $M$ that can be computed using a nondeterministic protocol with advise $\pi$ and one call to $\mathrm{EQ}$ oracle. Then for every $(a,b)$ such that $M(a,b) = 1$ (i.e. $(a,b)$ is in a connected component), there exists $\pi$ that covers (when represented as a graph) $(a,b)$; otherwise, if $M(a,b) = 0$, then $\pi$ does not cover $(a,b)$. Also, $\pi$ would be a biclique or $P_4$-free itself by the base case above; because, given $\pi$, no (additional) communication should be needed for Alice and Bob.

To formulate this idea precisely, we need a new definition:

Definition ($P_4$-free Cover Number). The $P_4$-free cover number of $G = (L,R,E)$, denoted $P_4\textsf{-fc}(G)$, is the minimum number of $P_4$-free graphs $G_i = (L,R,E_i)$ where $E = \bigcup_{i} E_i$.

We can also define the $P_4$-free partition number $P_4\textsf{-fp}(G)$ analogously, just like we defined biclique cover and partition numbers.

Basically, given $G$, we can decompose $G$ into $G_1, G_2 ,\dots, G_k$ such that $G_i$’s are $P_4$-free and they altogether cover $G$. The advise $\pi$ would be a number $\pi \in {1,2,\dots, k}$. Then Alice and Bob, upon receiving $G_{\pi}$, can compute their connected component $C_a$ and $C_b$ based on their input $a$ and $b$, and call the equality oracle $\mathrm{EQ}(C_a, C_b)$!

Theorem (Block et al. '21). Let $\Pi$ be the distribution of nondeterministic advise $\pi$ used in the nondeterministic protocol for $M$. Then $\lvert \mathrm{Supp}(\Pi) \rvert \geq P_4\textsf{-fc}(G)$; in other words, $$ \mathsf{NP}^{\mathsf{EQ}_{\mathsf{cc}}}(M) \leq \log_2 P_4\textsf{-fc}(G) $$

Note that the cover number $P_4\textsf{-fc}(G)$ is the correct model for this problem, not the partition number $P_4\textsf{-fp}(G)$; there could be more than one nondeterministic advise $\pi$ that can lead to the accepting calculation.

Not much is known on values of those numbers $P_4\textsf{-fc}(G)$ and $P_4\textsf{-fp}(G)$. But we know that we can construct a bipartite graph that has high $P_4$-free cover numbers, and the construction uses Zarankiewicz problem!

Theorem (Block et al. '21). There exists bipartite graphs $G = (L,R,E)$ with $\lvert L \rvert = N$ and $\lvert R \rvert = N$ whose $P_4\textsf{-fc}(G) \geq P_4\textsf{-fc}(G) \geq \varepsilon \cdot N^{1-2\varepsilon}$ for some $\varepsilon \in (0,1)$.

Proof (Sketch). At a high level, we shall construct a dense bipartite graph $G$ whose $P_4$-free subgraphs are sparse. Fix $t \in \mathbb{N}$ and let $G$ be a $K_{t+1,t+1}$-free graph, and consider its $P_4$-free subgraph, call it $H$.

Then, as discussed, $H$ would be a vertex-disjoint union of bicliques which, on the adjacency matrix, would be represented as rectangles. The dimensions (width and length) of each rectangle cannot be greater than $t$ at the same time: because otherwise it will correspond to a $K_{t+1,t+1}$. Let width be the shorter side and length be the longer side of a rectangle. By what we just discussed, a width should be $\leq t$ clearly, but the sum of lengths of all rectangles should be $\leq \lvert L \rvert + \lvert R \rvert = 2N$. From this, we can conclude that the number of edges of $H$ is $\leq 2Nt$. Then, by the averaging argument, $P_4\textsf{-fc}(G) \geq \lvert E \rvert / (2Nt)$.

Now we are left with estimating $\lvert E \rvert$. Because $G$ is $K_{t+1,t+1}$-free, $z(N,N;t+1,t+1)$ which, we can further lower bound using one of the known results we discussed: for some constant $C$,

\[z(N,N;t+1,t+1) \geq 2 \mathrm{ex}(N; K_{t+1,t+1}) \geq 2C N^{2 - \frac{(t+1) + (t+1) - 2}{(t+1)(t+1) - 1}} \geq 2C N^{2 - \frac{2}{t+2}}\]Therefore (WLOG $G$ is as dense as it can be, i.e. $\lvert E \rvert = z(N,N;t+1,t+1)$),

\[P_4\textsf{-fc}(G) \geq \frac{\lvert E \rvert}{2Nt} \geq \frac{2C N^{2 - \frac{2}{t+2}}}{2Nt} = \frac{C}{t} N^{2 - \frac{2}{t+2}} \geq \varepsilon N^{2 - \varepsilon}\]for some $\varepsilon \in (0, 1/3)$. $\blacksquare$

Further Readings

The main reference for this post is my notes (+ pictures on my phone) from our research meetings, which the part that this post pertains to should have been taken from:

Textbooks:

- Reinhard Diestel. Graph Theory (Springer GTM 173).

- Yufei Zhao. Graph Theory and Additive Combinatorics.

- Eyal Kushilevitz and Noam Nisan. Communication Complexity.

Research Papers:

- Alex Block et al. $P_4$-free Partition and Cover Numbers and Application. ITC '21.

- Lianna Hambardzumyan, Hamed Hatami, and Pooya Hatami. Dimension-free bounds and structural results in communication complexity. Israel Journal of Mathematics '23.

- Daniel Avraham and Amir Yehudayoff. On Blocky Ranks Of Matrices. Computational Complexity '24.

And by now, my notes should have mostly been subsumed by my labmate’s MS thesis:

- Daniel Yu-Long Xie. Breaking Graphs into Independent Rectangles. Master's Thesis. Purdue University, 2024.

Updated: